An (Over-Engineered) Clone of Apple's Scribble

Jan 26, 2026Updated: Jan 28, 2026

Intro

At the 2016 WWDC, Apple premiered a new way to communicate on Apple Watch called

Scribble.

Scribble lets you draft text messages by using your finger to draw text directly onto the small screen of the watch. While not the fastest way to communicate, it enabled quiet, accurate

writing under the constraints of the device: a small screen, weak processor, and

273 mAh battery.

This feature was super satisfying when it first came out. After 2 minutes of

playing with it, I just wanted to know how they did it! And to be honest, the precise answer

to that question still eludes me. But in this post, I’ll present one way to

recreate the same functionality, using the path of your mouse cursor as the

input.

It's important to caveat that I'm a hammer, and to me every nail looks like

a machine learning problem. In any case, I hope you'll find my solution fun and

straightforward. I'll continue building on this project as a test-bed for some

ideas in meta learning I'm eager to play with.

Try it out!

Checking API status...

This widget records your cursor's velocity as you drag it across the canvas and forwards

that data to

api.hectorastrom.com,

where the mouse velocity data is processed by a 1.0MB CNN hosted on an AWS

t3.small

instance in a couple of milliseconds. Most of the latency comes from the

back-and-forth between AWS and your browser. The (more accurate) 53-class

version doesn't support digits.####

How It Works

I don't actually know how scribble works on the Apple Watch - that's all

proprietary. It's certainly different from my version; after all, the engineers at

Apple were presented with much tighter constraints when building

their version than I was. However, that's also the reason this project could be built in a

few evenings of excited hacking, rather than by a team of payed engineers over XX months.

In this section, I'll describe how my version of scribble (the one you

tried above) works. This is a simple, fullstack ML project, but it's principles

& process are very universal. To see the code and read about my attempts, visit

the repo.

Pipeline

Scribble records mouse velocity data (either on device using

pynput, or in

browser with JavaScript), integrates the velocity data into positional data,

converts that positional data into a 28x28 image, and passes it through a

300K param CNN of 63 classes (a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and space). We sample the most likely

class as the character prediction.There are a couple oddities in that pipeline that deserve some justification:

- Why do we record with velocity, if we're integrating to position anyway?

- Why do we convert timeseries data to images, effectively throwing out a rich source of information about the path of the cursor?

The first oddity is a vestige of a constraint I was previously under: this

project started for a different purpose, where all data I had access to was mouse

velocities. The second oddity actually has a good explanation, and will become

clear in the training section.

Training

The training of the stroke classification model is broken into two phases:

- Pretraining on EMNIST

- Finetuning on my own mouse strokes

Pretraining

I wanted to get a prototype of scribble up fast, which meant offloading as

much of the work as possible to existing assets. Originally, I thought I could do

that by using lightweight OCR models. This worked terribly, because as it turns

out OCR models are built specifically for clean,

typed characters - not messy, continuous mouse strokes.

There was unfortunately no alphabetical character recognition model I could find

online, either. So, the laziest thing I could do next was use data that had already been collected.

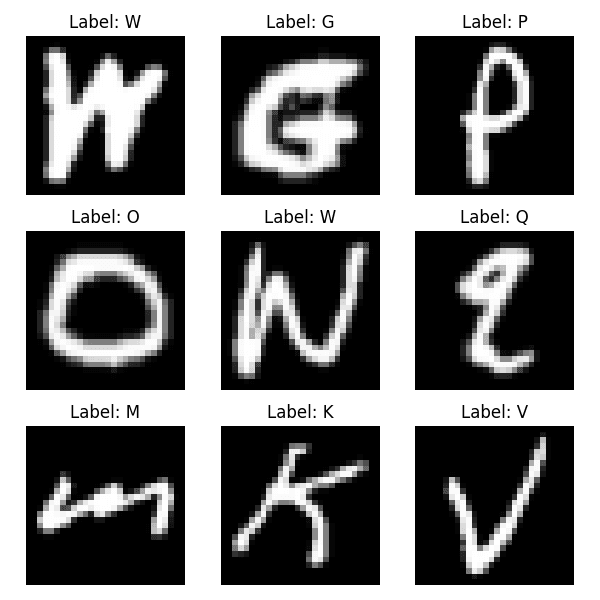

Thankfully, there's a dataset called EMINST that contains 814,000

28x28 B&W images

of handwritten letters and digits in the byclass split.

This dataset was perfect for my use case, and explains why I chose to use image

representations of mouse strokes instead of the timeseries versions: that's all

I had available for pretraining. So once I locked in that I'd be using a CNN for

this task, I could happily pretrain away.

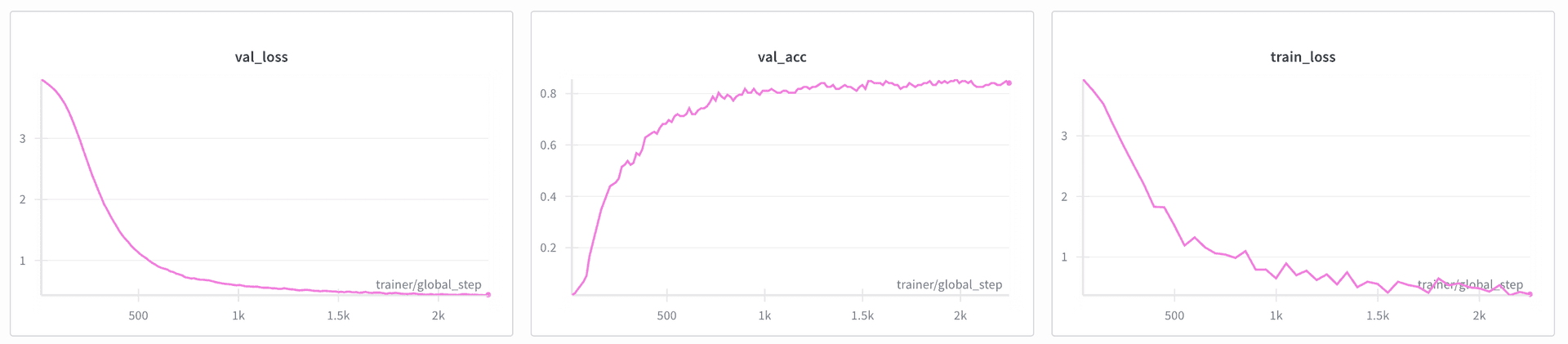

Pretraining takes ~20 minutes on my M2 Mac, and reaches an

87.5% offline test accuracy

in classifying the 62 characters available. I only needed to run this once.NOTE: Originally, I used the

letters split of the EMNIST dataset, which

combined lowercase and uppercase letter sketches with case-agnostic labels.

I've since revised this pretraining to use the byclass dataset, which is

both much larger, includes digits, and differentiates between upper and lowercase.Finetuning

I unfortunately couldn't stop right after pretraining because my desired domain

of continuously drawn characters

was slightly different from traditional handwritten characters. Mouse strokes are

continuous, messy, and

harder to differentiate. I sadly couldn't avoid collecting my own data.

After collecting 15-25 samples for each of the 63 characters, applying data

augmentation through the 200 epochs of training, and optimizing with a partial

finetune with a new classifer head, the model was ready!

Finetuning takes less than a minute, and boasts

80.9% offline test accuracy

(63-class) on

my mouse strokes.

Admittedly, the widget above feels worse than that. I attribute this

descreptancy to the slightly different domain in which strokes were collected

(see data collection below) and how they have to be drawn

back-to-back in the widget above. With a centered mouse and patient stroke, the

widget feels really accurate!Additional note - 53-class version: Originally, I had finetuned the model without digits, which is the 53-class

version in the widget above. This model boasted

92.9% test accuracy on the

53 classes. The 63-class version demonstrates substantially lower accuracy as

a consequence of both the larger class count and less effort to improve it

(updating to 63 classes is a new feature, with only one finetuning run completed).Data Collection

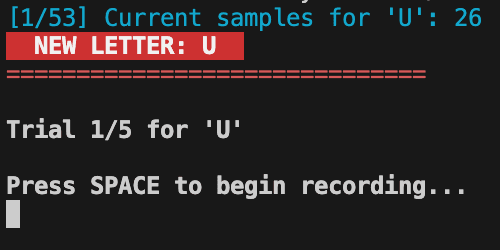

I really really hate data collection, but I do like making good tools. So I

tried to make the script for data collection as streamlined as possible.

After launching the data collection script, all you have to do is start a new

stroke with

space, draw the stroke you're told to draw, pause your mouse for

200ms and repeat. You can stim out pretty easy on this data collection, and it's

rewarding to know you're building a better model :)

The Model

Although I'm a deep learning guy at heart, this model is really simple. The

deployed version in the widget is a

300K parameter CNN, composed of three

convolutional blocks, with max pooling layers gluing them together. It takes the input image from

28x28 -> 1x1, and uses two-layer a classifier head trained with dropout.

Finetuning is done partially (relatively arbitrarily, I must admit; I didn't compare many

methods here), updating only block 3 and the classifer head in that

phase. The finetuning of the CNN reaches 80.9% performance from ~1200

training samples.Since it feels so bad to be throwing out the rich timeseries information from

a stroke, I did try using an LSTM, too. Unfortunately, this LSTM only

has the ~1000 samples that I personally collected for full training, as there's

no public, large-scale timeseries mouse stroke dataset I know of (HMU !)

This is an ongoing effort (attempt 3

here),

which -- at a dataset size of ~1000 -- attains

62% test accuracy. I would have thought

1000 timeseries samples would be enough to match CNN performance, but that was apparently too

optimistic. I'll continue working on this, but most likely the best action I

could take to improve LSTM performance is upload a page for all of you to

collect lots and lots of data for me ;) (coming soon...)####

Future of Scribble

scribble, at is current state, is a cool demo; but it doesn't provide value to

anyone. I could see scribble becoming a useful medium to interact with

computers for those with physical disabilities or those with fine motor

impairments.

scribble could also become a cool tool for everyone else. Effectively,

this software transforms the mouse into an additional input medium (imagine

being able to quickly execute a macro with a swipe of your mouse!)

Here are what I think the biggest limitations of scribble are, and how I

intend to solve them:

-

Images are a poor medium for rich, timeseries mouse velocity data

- See this third attempt!

-

Character recognition is best paired with natural language parser

- Pair the outputs & confidence levels from scribble with a language model, which votes on the plausability of certain strings based on its knowledge of complete words.

- Making this fast & on device is the real challenge -- I actually think this is a very hard problem.

-

Data collection needs to scale, a lot

- Make this software public & directly useful to automate large-scale data collection, so that people will want to use it give the model feedback (training data)

- Executing macros is one idea for a use-case

To be honest, though, scribble is in a fun, functional state so I felt

comfortable making it public to you all. It was an exciting thing to build after

school over a week, but is not the most impactful project of all time, nor

anything I intend to progress much further on its own.

The greatest value in scribble for me now is as a test-bed for some ideas in

meta-learning I want to try. It's a lot easier to test and feel a model

experiment here than with a bloated LLM or

BFM.

Last Thoughts

Like I said at the start, though, the process of building scribble is

identical to the process of building a model for any

machine-learning-amenable task. Whether it's mouse velocities, language tokens,

electrical brain activity, or photos, you'll discover this process is ubiqitous.

THE ML ENGINEERING RECIPE

- Decide what your task and goal is

- Figure out what data you have access to, and the cost to attain different

types of data

- Select the type that is both easiest to scale and highest signal-to-noise

- Design good representations & features for that data

- Select the best architecture for your data

- Mess around with this! It's the main researchy part, allowing for intellectual creativity

- Train the model (pretrain on whatever you can)

- Deploy & actually let people use it

Executing this process is just a muscle, but one that's starting to get really strong for

me.

It's the fundamentals that I used to dream about having when first starting to learn machine

learning, and enables me to work on a lot more complicated, experimental

research with confidence. That's the real reason I wrote this blog: to document

this recipe, applied to a task that everyone can play with.

Shoot me an email if you have thoughts for how to make scribble useful, if you

want to build anything out of it, or (especially!) to give feedback on my approach to

the solving problem.